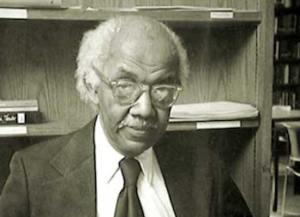

In the top left-hand corner of the EHSA’s 200th Anniversary Brochure is the photo of Allan Rohan Crite, EHS class of 1929, shown here. Perhaps not as recognizable as JP Morgan or other famous English High alums, Crite was an African-American artist whose contributions to the world of art are enormous.

Crite was born in New Jersey on March 20, 1910. The family relocated to Massachusetts and from the age of one until his death Crite lived in Boston’s South End.

His mother Annamae, was a poet who encouraged her son to draw. Showing promise at a young age, he enrolled in the Children’s Art Centre at United South End Settlements in Boston. His father, Oscar William Crite, was a doctor and an engineer, one of the first African-Americans to earn an engineering license.

After Crite’s graduation from English, he was admitted to the Yale School of Art but chose to attend the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and graduated in 1936. Recognition came early as well. Crite’s work was first shown at New York’s Museum of Modern Art in 1936. Crite then attended Harvard Extension School where he earned a BA degree in 1968.

Crite was among the few African-Americans employed by the Federal Arts Project. In 1940, he took a job as an engineering draftsman with the Boston Naval Shipyard and this supported his work as an artist for 30 years. He later worked part time as a librarian at Harvard.

Allan Rohan Crite in the 1980’s

In 1986, Boston named the intersection of Columbus Avenue and West Canton Street, steps from his home, Allan Rohan Crite Square. In 1993, Crite married Jackie Cox-Crite and together they established the Crite House Museum in their home at 410 Columbus Avenue in Boston’s South End.